Portret de Voluntar – Pille (Estonia)

[EN] My name is Pille Janson. I am 30 years old. I am from Estonia, where I lived in Uusküla, small village. I graduated from a Tallinn Service School. I have studied tourism and hospitality. I´m interested in different languages and cultures. I have studied also different languages: Finnish, Spanish and Russian. My family hosted exchange students from different countries now for three years. I like hiking, skating and skiing. I worked as a teacher assistant in the kindergarten. Also I have the same experience, when I was in the Armenia, where I made my short-term volunteering. I don’t have opportunity to work with school aged children but now I have this chance.

[RO] Numele meu este Pille Janson. Am 30 de ani. Sunt din Estonia, unde am locuit în Uusküla, oraș mic. Am absolvit la o Școală militară din Tallinn Service School. Am studiat turism și ospitalitate. Sunt interesată de diferite limbi și culturi. De asemenea am studiat diverse limbi: finlandeză, spaniolă și rusă. Familia mea a găzduit studenți de schimb din diferite țări de trei ani deja. Îmi plac drumețiile, patinajul și schiatul. Am lucrat ca asistent profesor la grădiniță. am de asemenea experiența deja, de când am fost în Armenia, unde mi-am făcut voluntariatul de scurt-timp. Nu aveam oportunitatea de a lucra cu copii de vârstă școlară dar acum am această șansă.

Pille este în România pentru o perioadă de opt luni, din ianuarie 2019 până în septembrie 2019, în cadrul proiectului Building Youth Supportive Communities – Environment [2017-2-RO01-KA105-037748] proiect co-finanțat de Uniunea Europeană prin Programul Erasmus+ și implementat în România de către Curba de Cultură.

Portret de Voluntar – Vitor (Portugalia)

Hello everyone, my name is Vítor or Simão as most people call me. I am 19 years old and I came from a town called Ermesinde in Porto.

Hello everyone, my name is Vítor or Simão as most people call me. I am 19 years old and I came from a town called Ermesinde in Porto.

I finished high school and before I moved on with my studies I wanted to gain some work experience so I went to work but I wasn’t happy with that and felt really frustrated with my work and myself so a few months later a friend of mine which did EVS in Bulgaria told me about it and I wanted to experience it.

I saw this Romanian project in Curba da Cultura and immediately I knew that I wanted to go to Romania, I love nature I love camping, hike and many other activities regarding nature mainly GeoCaching. So I came, I’m in Romania for three days and I’m absolutely loving it, for a Portuguese guy the snow is a new for me I only have seen it once when I was 8 so it was a long time ago. I’m currently living in Homorâciu a very rural village where life is simple and it’s really different for me because I’m a city boy but I just created two different hobby that are crack wood and start fire.

I love travel, meet cultures and learn new languages so I hope that at the end of my EVS I will be able to speak a little bit of Romanian because it sounds really interesting. I will try to learn everything I can from the Romanian culture and bring that to my country as well as leave a little bit of Portugal in Romania.

The plan after my EVS is to start my airline transport pilot licence(ATPL) which basically means that I want to become ani airline pilot. I have to thank everyone in Curba for being so kind to me and the rest of the volunteers as well.

Bună tuturor, numele meu este Vítor, sau Simão cum îmi spun majoritatea persoanelor. Am 19 ani și am venit dintr-un oraș numit Ermesinde din Porto.

Am terminat liceul și înainte de a merge mai departe cu studiile mele am vrut să câștig niște experiență de muncă, așa că am mers să lucrez dar nu am fost fericit cu asta și m-am simțit foarte frustrat cu munca mea și cu mine pentru câteva luni. Mai târziu, un prieten al meu care a făcut SEV în Bulgaria mi-a spus despre asta și am vrut să experimentez și eu.

Am văzut proiectul acesta românesc în Curba de Cultură și am știut imediat că am vrut să merg în România. Iubesc natura, iubesc excursiile cu cortul, drumețiile și multe alte activități legate de natură, în special GeoCaching-ul. Așa că am venit, sunt în România de trei zile și o absolut iubesc. Penteu un tip portughez zăpada este nouă pentru mine, am văzut-o doar o dată când aveam 8 ani deci a fost cu mult timp în urmă. Momentan locuiesc în Homorâciu, un sat foarte rural unde viața e simplă și e foarte diferit pentru mine penteu că sunt un băiat de oraș dar tocmai am creat două hobby-uri noi care sunt tăiatul de lemne și făcutul focului.

Iubesc călătoritul, să cunosc culturi și să învăț limbi noi așa că sper că la sfârșitul SEV-ului meu voi putea să vorbesc puțină română deoarece sună foarte interesant. Voi încerca să învăț tot ceea ce pot de la cultura românească și să aduc asta în țăra mea, precum și să las un pic de Portugalia în România.

Planul de după proiectul meu SEV este să îmi încep licența de pilot de transport aerian (ATPL) ceea ce practic înseamnă că vreau să devin pilot aerian. Am de mulțumit tuturor celor din Curba pentru că au fost așa de buni cu mine și celorlalți voluntari de asemenea.

Vitor este în România pentru o perioadă de opt luni, din ianuarie 2019 până în septembrie 2019, în cadrul proiectului Building Youth Supportive Communities – Environment [2017-2-RO01-KA105-037748] proiect co-finanțat de Uniunea Europeană prin Programul Erasmus+ și implementat în România de către Curba de Cultură.

Portret de voluntar – Roman (Germania)

Hello everybody,

Hello everybody,

I am Roman Lukas and i`m from Germany. I live in the city called Siegen. I am in Romania, Izvoarele, since two days and the rural area remindes me of the area where i`m coming from. In Germany, expecially in the area around Siegen, we do also have lots of trees, that`s something thats makes me feel like home at least a little bit.

I studied padagogy and i graduated with a Bachelor in 2012. After that i worked with people with mental diseases then i worked in the ambulant child- and youth welfare.

I quit my job because i wanted to try something new and i decided to go abroad to accept the challenges it might bring up. I think one of my biggest challange will be loosing the fear of dogs haha

I like listening to music and visiting concerts. I also like to watch movies or to read (i prepared myself for the journey by reading Herta Müller, who is a romanian/ german writer). Playing Soccer or Basketball is also one of my favorite activities.

In my time in Romania i want to learn a lot about the romanian culture and the people who are living here. I`m also interested in nature and i want to discover the romanian landscape.

So far, that`s enought about me. I will end with a quote:

” It`s better to burn out than to fade away” (Neil Young)

Bună tuturor,

Eu sunt Roman Lukas și sunt din Germania. Locuiesc în orașul numit Siegen. Sunt Izvoarele, România de două zile iar zona rurală îmi aduce aminte de zona de unde vin. În Germania, mai ales în zona din jurul Soegenului, avem de asemenea o grămadă de copaci, asta fiind ceva ce mă face să mă simt ca acasă măcar puțin.

Am studiat Pedagogie și am absolvit licență în 2012. După asta, am lucrat cu persoane cu boli mintale și apoi am lucrat în asistență socială ambulantă pentru copii și tineri.

Am demisionat de la slujba mea pentru că am vrut să încerc ceva nou și am decis să merg peste hotare să accept provocările pe care l-ar putea aduce. Cred că una dintre cele mai mare provocări pentru mine va fi săsscap de frica de câini haha.

Îmi place să ascult muzică și să merg la concerte. De asemenea îmi place să vizionez filme și să citesc (m-am pregătit de călătorie prin a citi Herta Müller, care este o scriitoare română/germană). Jucatul de fotbal și baschet sunt de asemenea unele dintre activitățile mele favorite.

În timpul meu în România vreau să învăț mult despre cultura română și despre oamenii care locuiesc aici. Sunt de asemenea interedat de natură și vreau să descopăr peisajul românesc.

Până acum, atât este suficient pentru mine. Voi încheia cu un citat:

” It`s better to burn out than to fade away” (Neil Young)

Roman este în România pentru o perioadă de opt luni, din ianuarie 2019 până în septembrie 2019, în cadrul proiectului Building Youth Supportive Communities – Environment [2017-2-RO01-KA105-037748] proiect co-finanțat de Uniunea Europeană prin Programul Erasmus+ și implementat în România de către Curba de Cultură.

Portret de Voluntar – Rita (Portugalia)

I’ve been asked to write or talk about myself too many times and every time you do it, you are not saying anything that is actually important, because what we say is how we want to be seen, perceived and not that many times what we think about ourselves and ultimately almost never who we are. My honesty always felt bad about this kind of thing, because if I get too honest people will probably have a hard time understanding me, if I am not I am going against what I believe. This is some sort of paradox, product of my own overthinking.

I’ve been asked to write or talk about myself too many times and every time you do it, you are not saying anything that is actually important, because what we say is how we want to be seen, perceived and not that many times what we think about ourselves and ultimately almost never who we are. My honesty always felt bad about this kind of thing, because if I get too honest people will probably have a hard time understanding me, if I am not I am going against what I believe. This is some sort of paradox, product of my own overthinking.

Once, a friend told me, to think about the things I put in my showcase. He thought that my decisions of what to put in it, like being scared of cats and not liking to climb stairs when they don’t seem safe, was not the most appealing information. So I decided to change it. In my showcase, in big letters, you can see now some things like THEATRE and READING. Also you will see TRAVELS and EXTREME CURIOSITY. WRITER.

I am from Portugal, that might be a good thing to keep there, doesn’t have to be in big letters anymore. I should also say I am 24 yo. I have a Degree in Theatre and I like to write, above everything else.

And that is about all I am going to say, for now. But sure will be posting soon, hopefully.

Mi-a fost cerut să scriu sau să vorbesc despre mine de prea multe ori și de fiecare dată când o fac, nu spun ceva ce e cu adevărat important, pentru că ceea ce spunem este cum vrem să fim văzuți, percepuți și nu de așa multe ori ceea ce credem despre noi înșine, și până la urmă aproape niciodată cine suntem. Onestitatea mea mereu s-a simțit rău în legătură cu astfel de lucruri, pentru că dacă sunt prea sinceră probabil oamenii vor avea dificultăți în a mă înțelege, dar dacă nu sunt merg împotriva a ceea ce cred. Acesta este un fel de paradox, produs al propriului meu gândit excesiv

Cândva, un prieten mi-a spus, să mă gândesc la lucrurile pe care le pun în vitrina mea. El credea că deciziile mele în legătură cu ceea ce să pun în ea, ca a fi speriată de pisici și a nu îmi plăcea să urc scări când nu par sigure, nu era cea mai atrăgătoare informație. Așa că am decis să o schimb. În vitrina mea, cu litere mari, poți vedea acum niște lucruri precum TEATRU și CITIT. De asemenea vei vedea CĂLĂTORII ȘI CURIOZITATE EXTREMĂ. SCRIITOR.

Sunt din Portugalia, acesta ar putea fi un lucru bun de ținut acolo, nu trebuie să mai fie în litere mari. Ar mai trebui și să spun că am 24 de ani. Am o diplomă în teatru și îmi place să scriu, mai presus decât orice.

Și asta este cam tot ceea ce am de gând să spun, penteu moment. Dar voi posta din nou curând, sper.

Rita este în România pentru o perioadă de opt luni, din ianuarie 2019 până în septembrie 2019, în cadrul proiectului Building Youth Supportive Communities – Environment [2017-2-RO01-KA105-037748] proiect co-finanțat de Uniunea Europeană prin Programul Erasmus+ și implementat în România de către Curba de Cultură.

Science of composting in simple terms – Compostul pe înțelesul tuturor

Composting

Have you ever heard about composting? No… well let me tell you what it is.

In the simplest terms it’s a cycle of life. Organic matters are naturally decomposed in a process called composting. This process recycles various organic materials or waste products and produces a soil conditioner (the compost).

Simpler? A tree or a vegetable, maybe a fruit will grow, fall on the ground and most likely by next year same time will turn into dirt – and not just simple dirt, it will be highly nutritious dirt, extremely good for plants to grow. So living things (plants and such) are with time becoming hummus (a really good dirt for plants), and if you gather it pile in order to get hummus, you can call it composting.

Now to business. Composting is highly recommended in agriculture. Some say that animals are the best fertiliser producers, but they are wrong: it is indeed good, but it contains a lot of acid so you need wait a few weeks or even months before using it as a compost. And not even mentioning the smell. So, a better, less smelly way to compost is to start a compost pile. It is easy and if done RIGHT it will not smell at all! Also on the benefits side: in some cases it takes only 2 weeks before getting good and usable compost (awesome right?).

What do you need for it?

Not much: you need space (depending how big is the compost pile).

Also you need food leftovers, as these will be the things you want to get rid of and turning it in green stuff, known as a nutrition for compost.

Another thing you need is referred to as brown stuff, that means old wood or paper, leaves that have turned to brown or old grass that is already brown. Brown stuff is a building block for composting.

Lastly it needs some air and water. These are quite important things for compost. Since composting is a chemical reaction between brown and green stuff, if it does not get enough of air it will create a lot of gas (and yes it smells). Also with reaction like this compost piles can become hot and I mean REALLY hot. (Ever heard a compliment “wow you are hotter than a compost pile”? ) There are cases where dry compost piles have thought on fire, since in summer, a good compost pile has steady degrees of 60 C, and if it is not touched in long time it can grow to about 80 degrees C easily.

Not to scare you, but no – the facts are not from some sort of science fiction movie, they are real.

OK, lets start with a compost pile.

step 1: find a place in the shade on the middle of the day. In my home I have 1m diameter of fence circle, on the shade of a apple tree.

step 1: find a place in the shade on the middle of the day. In my home I have 1m diameter of fence circle, on the shade of a apple tree.

step 2: start a kind of sandwich with brown stuff and green stuff. A compost pile is composed from 80% of brown stuff and 20%green stuff. Just imagine a sandwich from this and try to build one … you but a bit of brown stuff and add 1/4th of green stuff, on top of that again brown stuff, added 1/4 green stuff and so on. Some tips would be also try to always end with brown stuff so it would not attract animals or flies (also it will prevent it from smelling)

Taking care of a compost pile

General rule is – if it smells you messed it up. That means it might not have enough of air, or too much of green stuff, meaning not enough of brown stuff to decompose that smelly green stuff. Maybe your compost pile is black? That means its overheating and you need to stir it. Yes its best to stir your compost pile once a week so it would not over heat and maybe to take that precious nutrition rich dirt that your plants grave for so so so so much.

Urban compost

But wait! What if you live in a city and want to compost at home? There is an soulution. All yo u need is a bucket, green stuff (some food leftovers), a bit of brown stuff (a old news paper will do), some water and some WORMS. But not any worms: you need a handful of worms from special species and you problem is solved (for example red wigglers are most popular). These compost worms are awesome, they speed up composting remarkably and as result you can collect worm juice. All that these guys are doing is eating, reproducing and leaving behind their poo, so juice is actually their pee, one of the most powerful organic fertilisers. You have to mix it with water though, 10:1 for not killing the plant itself, as it it very concentrated.

u need is a bucket, green stuff (some food leftovers), a bit of brown stuff (a old news paper will do), some water and some WORMS. But not any worms: you need a handful of worms from special species and you problem is solved (for example red wigglers are most popular). These compost worms are awesome, they speed up composting remarkably and as result you can collect worm juice. All that these guys are doing is eating, reproducing and leaving behind their poo, so juice is actually their pee, one of the most powerful organic fertilisers. You have to mix it with water though, 10:1 for not killing the plant itself, as it it very concentrated.

So, when composting in the city all you need to do is to water the little guys, feed them every once in a while, have a bit of time to time gather the compost and juice, and ooh – make sure that they will not get direct sunlight as this is what kills them.

Yes and no in a compost pile

YES

- organic materials like leaves, grass, and food scraps (not oily!)

- newspapers (most inks used in newspapers are not toxic)

- tree bark

- all fruits and vegetables (including citruses)

- vegetable and fruit peels and ends

- coffee grounds and filters

- tea bags (even those with high tannin levels)

- grains such as bread, cracker and cereal (including moldy and stale)

- eggshells (rinsed)

- leaves and grass clippings (not sprayed with pesticides)

- paper towels (which has not been used with cleaners or chemicals)

NO

- meat and bones

- non organic waste as plastic

- oily materials

Compost

Ai auzit de compost? Nu… atunci dă-mi voie să îți spun ce este.

Pe scurt, este ciclul vieții. Materiile organice se descompun natural într-un proces numit compostare. Procesul reciclează variate materii organice sau resturi de produse și face un îngrășământ pentru sol (compost).

Mai simplu? Un copac ori o legumă, ori chiar un fruct va crește, va cădea pe pământ și până la anul va fi transformat în sol – și nu simplu sol, ci un sol cu proprietăți nutritive, extrem de bun pentru creșterea plantelor. Prin urmare ființele vii (plante și altele) se transformă în timp în humus (o materie foarte bună pentru plante), iar când aduni o astfel de grămadă de humus poți să o numești compost.

Compostul este foarte recomandat în agricultură. Unii zic că animalele sunt cei mai buni fertilizatori, dar se înșeală: sunt buni întradevăr, dar conțin mult acid, deci trebuie să aștepți câteva săptămâni sau chiar luni pentru a le folosi resturile ca și compost. Și să nu mai vorbim de miros. Un mod bun, mai puțin mirositor de a face compost este să faci o grămadă de compost. E ușor și dacă e făcut CORECT nu va mirosi deloc! Printre beneficii: în unele cazuri durează doar 2 săptămâni pentru a avea compost bun de folosit (minunat, nu?).

De ce ai nevoie?

Nu foarte multe: spațiu (depinde cât de mare e grămada de compost). Și mai ai nevoie de resturi alimentare, că astea sunt cele de care vrei să scapi, sunt chestiile verzi pe care le transformi în resurse pentru compost. Și mai ai nevoie de chestii maro, lemn vechi sau hârtie, frunze sau iarbă maro deja. Acestea sunt baza compostului.

Și în cele din urmă ai nevoie de aer și apă. Și astea sunt destul de importante pentru compost. Din moment ce compostarea este o reacție chimică între materiile maro și cele verzi. Dacă nu are suficient aer se vor crea gaze (și va mirosi). Totodată în reacțiile dintr-o grămadă de compost poate deveni foarte fierbinte. (Ai auzit vreodată de complimentul “ești mai fierbinte decât o grămadă de compost”?). Au fost cazuri în care grămezi uscate de compost au luat foc, căci pe timp de vară, o grămadă de compost are o temperatură constantă de 60 grade C și dacă nu este atinsă o perioadă poate ajunge la 80, cu ușurință.

Nu intenționez să te sperii, dar astea sunt fapte reale și nu filme science fiction.

OK, să facem o grămadă de compost.

Pasul 1: găsește un loc care e la umbră în miezul zilei. Acasă am un spațiu de 1 metru diametru îngrădit cu un gard, sub un măr.

Pasul 2: fă un sandviș cu materii maro și verzi. O grămadă de compost are 80% materii maro și 20% materii verzi. Imaginează-ți un sandviș din astea și fă unul. Deci materii maro și 1/4 materii verzi și apoi din nou maro și din nou versi. Un sfat, încheie cu materii maro, ca să nu atragi animale sau muște și pentru a nu mirosi.

Îngrijirea unei grămezi de compost

Regulă generală – dacă miroase ceva a mers prost. Adică ori nu a avut suficient aer, ori prea multe materii verzi și prea puține maro în care să se descompună. Poate grămada ta de compost e neagră? Asta înseamnă că s-a supraîncălzit și trebuie să o amesteci. Da, e bine să amesteci grămada de compost o dată pe săptămână, pentru a nu se încăzi prea tare și a distruge elementele nutriționale de care plantele tale au nevoie.

Compost urban

Dar stai! Dacă locuiești într-un oraș și vrei să faci compost? Există o soluție. Tot ce ai nevoie este o găleată, materii verzi (resturi alimentare), ceva materii maro (ziare vechi) niște apă și ceva viermi: ai nevoie de o mână de viermi dintr-o specie specială și problema ta este rezolvată (râmele sunt cele mai populare). Acești viermi pentru compost sunt minunați, ei grăbind procesul de compostare și ca rezultat poți aduna și un fel de suc. Tot ce fac vermii ăștia este să mănânce, să se reproducă și să lase în urma lor fecale și urină, urina fiind unul dintre cele mai puternice fertilizatoare. Totuși trebuie să o amesteci cu apă în proporție de 10:1, dacă nu vrei să distrugi plantele.

Deci, când faci compost în oraș nu trebuie decât să le dai apă acestori viermi și să îi hrănești din când în când, apoi să aduni compostul și sucul și să te asiguri că nu ajung în lumina directă a soarelui, căci îi va ucide.

Ce să pui și să nu pui în grămada de compost

DA

- materii organice precum frunze, iarbă și coji de fructe (care nu sunt uleioase)

- ziare (majoritatea cernelurilor nu sunt toxice)

- scoarță de copac

- fructe și legume (incluzând citrice)

- coji și cotoare de fructe și legume

- zaț de cafea și filtre

- pliculețe de ceai (chiar și cele cu conținut ridicat de tanin)

- produse de panificație, pâine, biscuiți, cereale (inclusiv cele mucegăite și învechite

- coji de ouă (clătite)

- resturi de iarbă și frunze (care nu au fost ierbicidate)

- prosoape de hârtie (care nu au fost folosite împreună cu chimicale)

NU

- caren și oase

- resturi non-organice (plastic de exemplu)

- materii uleioase

Raimo este în România pentru o perioadă de șapte luni, din mai 2018 până în noiembrie 2018, în cadrul proiectului Building Youth supportive Communities – Environment [2017-2-RO01-KA105-037748] proiect co-finanțat de Uniunea Europeană prin Programul Erasmus+ și implementat în România de către Curba de Cultură.

A little story about paper – O mică poveste despre hârtie

/EN/

Howdy!

Coming from Germany, I am very used to recycling, especially when it comes to paper. Germans recycle about 80% of all their paper, meanwhile the recycling of paper is nearly non-existent in Romania.

But why go though all the work of carefully selecting the paper and recycling it to new paper? Unlike plastic or metal products, paper is made out of wood which can easily be regrown.

One big reason would be in order to save water. The production of 40g new paper needs 2,8 L of water, compared to 0,2 L for recycling paper. It also becomes a lot more polluted in the process of producing new paper, than in the one for recycled paper. If you are interested in finding out why saving water is so important for the environment, read Robert’s article about water, coming up in the next days.

Another point is, that the chemicals used in order to make paper out of wood are often very toxic and bad for the environment, unlike the ones used for the recycling process. This is especially true for the bleaching of newly made paper, which is either not done with recycling paper or done with non-toxic chemicals.

The recycling process for paper also needs 1/3 of the energy of producing newly made paper.

It also needs wood. While trees can be regrown, it takes years for them to do so and if we use up to much wood to regrow, the amount of forests in a country decrease and decrease, as is currently the case in Romania.

If you want to help the environment, try to sort paper and put it into the blue recycling bin, buy recycling paper instead of normal one and use both sides of paper.

And here is a little guide for recycling paper yourself:

- Put small pieces of paper [tear them apart by hand] into a bucket of water and leave it alone for three days

- Nail a fly screen onto a wooden frame (about the size of a piece of paper)

- Blend the water-paper-mix with a blender. If the mass is to solid, add warm water.

- Put the paper-mix into a big container, add water (About a quater of the paper mass). Take the frame from step 2 and pull it slowly though the water, till their is a small layer of paper on it.z

- Tear the layer slowly from the frame and leave it to dry

/RO/

Servus!

Venind din Germania sunt obișnuită să reciclez, mai ales hârtie. Nemții reciclează în jur de 80% din hârtie, în timp ce reciclarea hârtiei în România e aproape inexistentă.

Dar de ce să trecem prin acest proces de selectare a hârtiei și reciclare? Spre deosebire de plastic și metal, hârtia e făcută din lemn, care poate fi înlocuit prin plantare.

Un motiv important pentru a recicla este pentru a economisi apă. Pentru a produce 40gr de hârtie nouă e nevoie de 2.8L apă, în timp ce pentru aceeași cantitate prin reciclare e nevoie de 0.2L. De asemenea apa devine mai poluată la finalul acestui proces, decât cea folosită la reciclare. Dacă vreți să aflați mai multe despre importanța apei pentru mediu, citiți articolul lui Robert (urmează în următoarele zile, fiți pe faza).

Un alt motiv ar fi chimicalele folosite pentru a crea hârtie, care sunt adesea toxice și nocive pentru mediu, spre deoasebire de cele pentru reciclare. Asta mai ales din cauza înălbitorilor folosiți pentru hârtie, care nu sunt folosiți la hârtia reciclată, ori sunt folosiți unii non-toxici.

În plus, procesul de reciclare a hârtiei are nevoie de doar o treime din energia folosită pentru hârtia nouă. Apoi mai are nevoie de lemn. Chiar dacă pădurile pot refăcute, durează ani de zile pentru acest lucru, iar dacă folosim pădurile prea mult, zonele împădurite scad vizibil, cum e cazul României.

Dacă vrei să ajuți mediul, încearcă să sortezi hârtia și pune-o în containerul albastru, cumpără hârtie reciclată în loc de cea obișnuită și mai ales folosește ambele părți ale hârtiei.

Aici aveți un mic ghid de reciclare a hârtiei:

- Pune bucățele de hârtie (rupte cu mâna) într-o găleată cu apă și lasă-le trei zile.

- Prinde o pânză de țânțari pe o ramă de lemn (de mărimea hârtiei pe care vei să o produci)

- Amestecă compoziția de hârtie cu apă cu un blender. Dacă e prea tare, mai pune puțină apă caldă.

- Transferă amestecul într-un vas mai mare și mai pune apă (un sfert din cantitatea de hârtie). Ia rama de la punctul 2 și trece-o ușor prin apă, până ai un mic strat de hârtie pe ea.

- Desfă stratul ușor de pe ramă și lasă-l să se usuce.

Milena este în România pentru o perioadă de cinci luni, din iulie 2018 până în noiembrie 2018, în cadrul proiectului Building Youth supportive Communities – Environment [2017-2-RO01-KA105-037748] proiect cofinanțat de Uniunea Europeană prin Programul Erasmus+ și implementat în România de către Curba de Cultură.

Why do we need forests and how can we keep them / De ce avem nevoie de păduri și cum putem să le păstrăm

[EN] I can’t remember if there was a time when I wasn’t in love with nature, could be because I grew up in a place where I could play among the trees anytime I wanted. I come from a small country in central Europe called Slovenia and the thing I adore most about it is the fact that 66% of it is covered by forests. Those provide a vital environment for many species. There are over 3000 different fern and flower species along with 50000 different animal species thriving in my country so I’m very happy that over 11% of our land is protected territory.

Upon my arrival in Romania I was initially shocked by the vast flat-lands but in a country as big as Romania is I was sure to find some landscapes more suitable for my soul. It comes as no surprise the country has plenty of green forests to offer. Not only that, there are 3,700 plant species identified, out of which 23 are declared natural monuments, 74 are extinct species, 39 are endangered species, 171 are vulnerable species and 1253 rare species. 33.792 animal species have been identified, out of which 33.085 invertebrates and 707 vertebrates. So there are a lot of reasons to protect the natural environment, not only in my country and Romania but also everywhere else.

But a question comes to mind: how? How can you as an insignificant individual help something so ancient and bigger than you can imagine? Surely none of us will single-handedly prevent climate change, deforestation and pollution, but every little bit helps. The easiest way and the one that unfortunately doesn’t pop into everyone’s mind is simple: just don’t throw your trash on the floor after you no longer need it. If you were able to carry the package of chips with you before it was empty how can you not take the empty one back to the nearest bin? Using recycled paper also helps a lot as no new trees were cut down to help you with your daily lives.

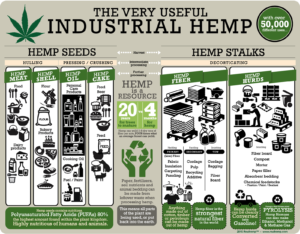

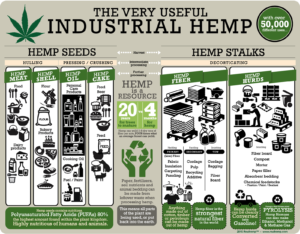

Hemp products are also a very good alternative as the plant gives valuable resources in a shorter time; it also isn’t very demanding and doesn’t exhaust the soil as much. With wide variety of use it truly is a great choice, from food to building material: is there anything it can’t do?

Another simple solution is to opt for a walk or ride on a bicycle instead of taking a car, using public transportation instead of a personal vehicle also doesn’t seem as much but definitely helps.

But back to my main point: why do we need trees in the first place? It’s not only because they are nice to look at, even though studies showed patients with a green view had a quicker recovery. The obvious reason is because they produce oxygen and well, that’s literally something you can’t live without, them filtering over 21 kg of carbon dioxide per year (a single tree) is also pretty amazing.

The root system prevents soil erosion, their shade can help cool down urban areas, also saving you money on cooling down your house in summer and providing protection from winds which can help lower costs of your winter heat bill. Air pollution isn’t the only pollution they help with, noise pollution is also lowered in areas with trees. To top it off just think about all the food they provide, from fruits to syrup and playing a vital role in honey production. There are also medicinal properties that can be extracted from a number of trees (apple tree, common ash, hazel, beech tree, cedar and black walnut just as an example). So on your next walk through the woods I hope you will see these ancient beauties as the amazing living things they are and will be mindful of your surrounding. Plus points if you take out more trash than you brought. Thanks for your read, hope to talk to you soon, hugs and kisses until then.

[RO] Nu-mi pot aminti dacă era un timp când nu eram îndrăgostit de natură, ar putea fi pentru că am crescut într-un loc unde m-am putut juca printre copaci oricând am vrut. Vin dintr-o țară mică din Europa centrală numită Slovenia, iar lucrul pe care îl ador cel mai mult la ea este faptul că 66% din ea este acoperită de păduri. Acestea asigură un mediu vital pentru multe specii. Există peste 3000 de specii diferite de ferigi și flori pe lângă 50000 de specii diferite de animale prosperând în țara mea așa că sunt foarte fericit că peste 11% din țara noastră e teritoriu protejat.

La sosirea mea în România am fost inițial șocat de vastele câmpii, dar într-o țară așa mare cum e România eram sigur că o să găsesc niște peisaje mai potrivite pentru sufletul meu. Nu a venit ca o surpriză că țara are o grămadă de păduri verzi de oferit. Nu numai asta, sunt 3,700 de specii de plante identificate, dintre care 23 sunt declarate monumente naturale, 74 sunt specii extincte, 39 sunt specii pe cale de dispariție, 171 sunt specii vulnerabile și 1253 specii rare. 33.792 de specii de animale au fost identificate, dintre care 33.085 nevertebrate și 707 vertebrate. Așa că sunt o grămadă de motive să protejezi mediul natural, nu numai în țara mea și în România dar de asemenea în toate celelalte locuri.

Dar o întrebare vine în minte: cum? Cum poți tu ca un individ insignifiant să ajuți ceva așa de străvechi și mai mare decât îți poți imagina? Cu siguranță nici unul dintre noi nu va preveni de unul singur schimbarea climatică, defrișările și poluarea, dar fiecare lucru micuț ajută. Cel mai ușor mod și cel care din păcate nu apare în mintea tuturor e cel mai simplu: doar nu arunca gunoiul pe jos după ce nu mai ai nevoie de el. Dacă ai putut să cari pachetul de chipsuri cu tine înainte să fie gol cum poți să nu îl iei pe cel gol înapoi la cel mai apropiat coș? Folosirea hârtiei reciclate de asemenea ajută mult căci nici un nou copac nu este tăiat pentru a te ajuta cu viața de zi cu zi.

Produsele din cânepă sunt de asemenea o alternativă foarte bună, planta dând resurse valoroase într-un timp mai scurt; de asemenea nu necesită foarte multe resurse și nu extenuează solul la fel de mult. Cu o varietate largă de folosiri e cu adevărat o alegere minunată, de la mâncare la material de construcții: e ceva ce nu poate să facă?

O altă soluție simplă este să optezi pentru a merge sau a face o plimbare cu bicicleta în loc de a lua mașina, de a folosi mijloacele de transport în comun în loc de un vehicul personal de asemenea nu pare de parcă e așa mare lucru dar ajută cu certitudine.

Dar înapoi la principalul meu punct: de ce avem nevoie de copaci de fapt? Nu e numai pentru că sunt frumoși când te uiți la ei, deși studii au arătat că pacienții cu o priveliște verde au avut o recuperare mai rapidă… Motivul evident este pentru că produc oxigen și ei bine, asta e literalmente ceva fără de care nu poți trăi, ei filtrând peste de 21 kg de dioxid de carbon pe an (un singur copac) e deasemenea destul de uimitor.

Sistemul de rădăcini previne eroziunea solului, umbra lor poate ajuta la răcirea zonelor urbane, de asemenea salvându-ți banii la a îți răci casa vara și asigurând protecție împotriva vântului ceea ce poate ajuta la micșorarea costurilor facturii tale de iarnă. Poluarea aerului nu e singura poluare cu care ajută, poluarea fonică e de asemenea micșorată în zone cu copaci. Peste toate astea doar gândește-te la toată mâncarea pe care o asigură, de la fructe la sirop și jucând un rol vital în producția de miere. Sunt de asemenea proprietăți medicinale care pot fi extrase dintr-un număr de copaci (măr, frasin comun, castan, fag, cedru și nuc negru doar ca un exemplu). Deci următoarea ta plimbare prin pădure sper că vei vedea aceste frumuseți antice ca pe minunatele lucruri vii care sunt și vei fi atent la împrejurimile tale. Puncte în plus dacă pleci cu mai mult gunoi decât ai adus. Mulțumesc pentru lectură, sper să vorbim curând, îmbrățișări și pupici până atunci.

Robert este în România pentru o perioadă de cinci luni, din iulie 2018 până în noiembrie 2018, în cadrul proiectului Building Youth supportive Communities – Environment [2017-2-RO01-KA105-037748] proiect cofinanțat de Uniunea Europeană prin Programul Erasmus+ și implementat în România de către Curba de Cultură.

Small everyday things that make a difference for the planet / Mici lucruri din viața de zi cu zi care fac o diferență pentru planetă

[EN] Embarking on an environmental volunteering project is something very personal. This is not a regular job that I do from 8 to 5 and forget about it for the rest of the day. It reflects my values, my desired way of life. Therefore, when I came to Romania and started working on this project, I also started thinking about my daily life and my routines. And I discovered plenty of situations where I was behaving unsustainably, because of routines that I follow without thinking, and things I do out of laziness or comfort or because I simply don’t know any other solution. And so, I started observing and changing small things in my daily life. At first it seemed to be a big deal to change routines, but if done in the right way, step by step the new behaviour becomes the routine, and things are getting done automatically.

But let’s keep it concrete, and stick to some examples from my daily life here in Izvoarele.

When I moved in, recycling was something that was done, but not well done. The closest recycling bins are 700 meters away, so it was easier to throw most of the stuff into the wet waste, which is collected once a week. All you have to do is to put the container on the street. And although I was used to recycling back home in Portugal, I found myself adapting to my housemates’ behaviour. When the commune introduced the blue bags for plastic and metal that are collected every two weeks, we took it as an impetus to rethink our household and started separating wet waste, organic, blue bag, glass and paper. All it took was to think a bit about what waste we produce and where in the house.

When I moved in, recycling was something that was done, but not well done. The closest recycling bins are 700 meters away, so it was easier to throw most of the stuff into the wet waste, which is collected once a week. All you have to do is to put the container on the street. And although I was used to recycling back home in Portugal, I found myself adapting to my housemates’ behaviour. When the commune introduced the blue bags for plastic and metal that are collected every two weeks, we took it as an impetus to rethink our household and started separating wet waste, organic, blue bag, glass and paper. All it took was to think a bit about what waste we produce and where in the house.

The main stake of our waste is produced while cooking/eating, so placing the organic waste and recycling bins in the kitchen or nearby makes sense. If they are on the other side of the house, the trash is more likely to end in the wet waste that is handily located under the sink. After all, in our daily routines we intuitively do the easiest and most comfortable thing.

We have a dog, so it makes sense to have a bin for the empty food cans and bags somewhere near the feeding bowl. In the rooms, the trash mainly consists of old papers and bills, so we put small boxes for paper there. We also put a box in the bathroom for the empty toilet paper rolls. Once we figured where to put which bins, recycling became an easy task, a natural routine.

We have a dog, so it makes sense to have a bin for the empty food cans and bags somewhere near the feeding bowl. In the rooms, the trash mainly consists of old papers and bills, so we put small boxes for paper there. We also put a box in the bathroom for the empty toilet paper rolls. Once we figured where to put which bins, recycling became an easy task, a natural routine.

Some of the materials we consider waste are actually reusable. For example, whenever I am going somewhere and need to take something to drink, I fill a glass bottle with tap water. And we save all the jars, wash them and put jam or other stuff inside. Paper is saved to start fire in the ovens in winter, carton boxes are used for shopping and to collect fruits.

As we decided to collect our organic waste separately, the question arose of what to do with it as there is no separate collection of organic waste in Romania (currently, in only 8 European countries organic waste is collected by the communes [1]). But as we live on the countryside and have a big garden, we decided to start composting.

Our garden has some fruit trees, and lately we have been flooded with pears, apples and prunes. Adrianna started to make jam and compote out of them. And there is no reason why we shouldn’t: it’s free, it’s healthy, it’s tasty. But well, it requires work. And when Adrianna left, no one took over this task, so that a lot of the fruits were just rotting on the ground. At some point we started picking them up and storing them in the basement (hoping that it is cold and dry enough) and we figured out that it is not that hard to handle them. There are plenty of ways to make them storable: besides jam and compote, we can make dry fruits, juice, pies…

Our garden has some fruit trees, and lately we have been flooded with pears, apples and prunes. Adrianna started to make jam and compote out of them. And there is no reason why we shouldn’t: it’s free, it’s healthy, it’s tasty. But well, it requires work. And when Adrianna left, no one took over this task, so that a lot of the fruits were just rotting on the ground. At some point we started picking them up and storing them in the basement (hoping that it is cold and dry enough) and we figured out that it is not that hard to handle them. There are plenty of ways to make them storable: besides jam and compote, we can make dry fruits, juice, pies…

Not everyone has the garden, the patience or the time to grow their own food, but still we can be aware of what we eat and ask ourselves if it is worth buying imported products if there are national, even local ones available. Buying local products reduces the pollution from transport, besides helping the local economy. And so, slowly I grew the habit of checking the labels to see where the products come from. And at one point I decided to buy only fruits and vegetables grown in Romania, and after a while I extended this to dairy products and meat. I also started to go to the market and the butcher, as there the chances are higher to get local products.

Another important part of our daily routines is the way to work. In Portugal I mainly used the bicycle in my daily life, but in Izvoarele the roads are either full of traffic or in a desolate state. But walking to work turned out to be a good option as well, it frees my mind and it is healthy both for me and for the environment.

Of course, there are a lot more things that I can change in my daily life. My next goal is to reduce the amount of plastic waste I produce, so I will start bringing my own bags to the market, looking for eco-friendlier packaged products, and so on.

[1] https://www.compostnetwork.info/policy/biowaste-in-europe/separate-collection/

[RO]

Îmbarcarea într-un proiect de voluntariat în domeniul mediului e ceva foarte personal. Ăsta nu este un loc de muncă obișnuit la care mă duc de la 8 la 5 și de care uit pentru restul zilei. Îmi reflectă valorile, felul de viață pe care doresc să îl trăiesc. Așadar, când am venit în România și am început să lucrez la acest proiect, am început de asemenea să mă gândesc la viața mea de zi cu zi și la rutinele mele. Și am descoperit o mulțime de situații unde mă comportam nesustenabil, din cauza unor rutine pe care le aveam fără să mă gândesc la ele, și lucruri pe care le fac din lene sau comfort sau pentru că pur și simplu nu știu altă soluție. Și deci, am început să observ și să schimb mici lucruri în viața mea de zi cu zi. La început a părut să fie mare lucru să schimb rutine, dar dacă e făcut în modul potrivit, pas cu pas noul comportament devine rutină, iar lucrurile sunt făcute automat.

Dar să o ținem concret, și să rămânem pe niște exemple din viața mea de zi cu zi aici în Izvoarele.

Când m-am mutat aici, reciclarea era ceva ce se făcea, dar nu se făcea bine. Cele mai apropiate coșuri de reciclare sunt la 700 de metri depărtare, așa că era mai ușor să arunc majoritatea lucrurilor în gunoiul menajer, care este colectat o dată pe săptămână. Tot ce trebuie să faci este să pui containerul pe stradă. Și deși eram obișnuit cu reciclarea acasă în Portugalia, am început să mă adaptez la comportamentul celor cu care locuiam. Când comuna a introdus sacii albaștrii pentru plastic și metal care sunt colectați odată la două săptămâni, am luat-o ca pe un imbold să regândim gospodăria noastră și am început să separăm gunoiul menajer, organic, sacul albastru, sticlă și hârtie. Tot ce a fost nevoie a fost să ne gândim puțin la ce gunoi producem și unde anume în casă.

Când m-am mutat aici, reciclarea era ceva ce se făcea, dar nu se făcea bine. Cele mai apropiate coșuri de reciclare sunt la 700 de metri depărtare, așa că era mai ușor să arunc majoritatea lucrurilor în gunoiul menajer, care este colectat o dată pe săptămână. Tot ce trebuie să faci este să pui containerul pe stradă. Și deși eram obișnuit cu reciclarea acasă în Portugalia, am început să mă adaptez la comportamentul celor cu care locuiam. Când comuna a introdus sacii albaștrii pentru plastic și metal care sunt colectați odată la două săptămâni, am luat-o ca pe un imbold să regândim gospodăria noastră și am început să separăm gunoiul menajer, organic, sacul albastru, sticlă și hârtie. Tot ce a fost nevoie a fost să ne gândim puțin la ce gunoi producem și unde anume în casă.

Cea mai mare porțiune din gunoiul nostru este produs gătind/mâncând, așa că să poziționăm deșeurile organice și coșurile de reciclare în bucătărie sau în apropiere are sens. Dacă se află în cealaltă parte a casei, gunoiul e mult mai probabil să ajungă în gunoiul menajar care e localizat la îndemână sub chiuvetă. La urma urmelor, în rutina noastră zilnică facem intuitiv cel mai ușor și mai comfortabil lucru.

Avem un câine, așa că are sens să avem un coș pentru conservele și pungile goale de mâncare undeva lângă bolul unde îl hrănim. În camere, gunoiul e constituit în principal din hârtii vechi și facturi, așa că am pus mici cutii pentru hârtie acolo. Am pus de asemenea o cutie în baie pentru rolele goale de hârtie igienică. Odată ce ne-am dat seama unde să punem care coșuri, reciclarea a devenit o sarcină ușoară, o rutină ce ne vine în mod natural.

Avem un câine, așa că are sens să avem un coș pentru conservele și pungile goale de mâncare undeva lângă bolul unde îl hrănim. În camere, gunoiul e constituit în principal din hârtii vechi și facturi, așa că am pus mici cutii pentru hârtie acolo. Am pus de asemenea o cutie în baie pentru rolele goale de hârtie igienică. Odată ce ne-am dat seama unde să punem care coșuri, reciclarea a devenit o sarcină ușoară, o rutină ce ne vine în mod natural.

Unele din materialele pe care le considerăm gunoi sunt de fapt refolosibile. Spre exemplu, de fiecare dată când merg undeva și am nevoie să iau ceva de băut, umplu o sticlă de sticlă cu apă de la robinet. Și păstrăm toate borcanele, le spălăm și punem gem sau alte lucruri înăuntru. Hârtia este păstrată pentru a porni focuri în sobe iarna, cutiile de carton sunt folosite pentru cumpărături și pentru a colecta fructe.

Având în vedere că am decis să ne colectăm deșeurile organice separat, a răsărit întrebarea ce să facem cu ele având în vedere că nu există colectare separată a deșeurilor organice în România (în mod curent, în doar 8 țări Europene deșeurile organice sunt colectate de autorități locale [1]). Dar cum locuim la țară și avem o grădină mare, am decis să începem să facem compost.

Grădina noastră are niște pomi fructiferi, și în ultima vreme am fost inundați cu pere, mere și prune. Adrianna a început să facă gem și compot din ele. Și nu e nici un motiv pentru care nu am face: e gratis, e sănătos, e gustos. Dar, însă, necesită muncă. Și când Adrianna a plecat, nimeni nu a preluat această sarcină, așa că o grămadă din fructe pur și simplu putrezeau pe jos. La un moment dat am început să le adunăm și să le depozităm în pivniță (sperând că e suficient de rece și uscat) și ne-am dat seama că nu e așa greu să ne ocupăm de ele. Există destule feluri prin care să le facem depozitabile: pe lângă gem și compot, putem face fructe uscate, suc, plăcinte…

Grădina noastră are niște pomi fructiferi, și în ultima vreme am fost inundați cu pere, mere și prune. Adrianna a început să facă gem și compot din ele. Și nu e nici un motiv pentru care nu am face: e gratis, e sănătos, e gustos. Dar, însă, necesită muncă. Și când Adrianna a plecat, nimeni nu a preluat această sarcină, așa că o grămadă din fructe pur și simplu putrezeau pe jos. La un moment dat am început să le adunăm și să le depozităm în pivniță (sperând că e suficient de rece și uscat) și ne-am dat seama că nu e așa greu să ne ocupăm de ele. Există destule feluri prin care să le facem depozitabile: pe lângă gem și compot, putem face fructe uscate, suc, plăcinte…

Nu toată lumea are grădina, răbdarea sau timpul să își crească propria mâncare, însă tot putem fi conștienți de ceea ce mâncăm și ne putem întreba dacă merită să cumpărăm produse importate dacă sunt unele naționale, chiar locale disponibile. Cumpăratul de produse locale reduce poluarea din transport, pe lângă că ajută economia locală. Și așadar, încetișor am dezvoltat obiceiul de a verifica etichetele pentru a vedea de unde vin produsele. La un moment dat am decis să cumpăr doar fructe și legume crescute în România, și după o vreme am extins asta și la produse lactate și carne. Am început de asemenea să mă duc la piață și la măcelar, șansele de a găsi produse locale fiind mai mari acolo.

O altă parte importantă din rutina noastră zilnică este drumul către muncă. În Portugalia foloseam în principal bicicleta în viața mea de zi cu zi, dar în Izvoarele drumurile sunt ori pline de trafic ori într-o stare proastă. Dar mersul pe jos la muncă s-a dovedit a fi o opțiune bună de asemenea, îmi eliberează mintea și este sănătos atât pentru mine cât și pentru mediu.

O altă parte importantă din rutina noastră zilnică este drumul către muncă. În Portugalia foloseam în principal bicicleta în viața mea de zi cu zi, dar în Izvoarele drumurile sunt ori pline de trafic ori într-o stare proastă. Dar mersul pe jos la muncă s-a dovedit a fi o opțiune bună de asemenea, îmi eliberează mintea și este sănătos atât pentru mine cât și pentru mediu.

Desigur, mai sunt multe lucruri pe care le pot schimba în viața mea de zi cu zi. Următorul meu țel este să reduc cantitatea de deșeuri din plastic pe care o produc, așa că voi începe să îmi aduc propriile pungi la magazin, mă voi uita după produse ambalate mai prietenoase cu mediul (eco-friendly), și așa mai departe.

[1] https://www.compostnetwork.info/policy/biowaste-in-europe/separate-collection/

Tim este în România pentru o perioadă de șapte luni, din mai 2018 până în noiembrie 2018, în cadrul proiectului Building Youth supportive Communities – Environment [2017-2-RO01-KA105-037748] proiect co-finanțat de Uniunea Europeană prin Programul Erasmus+ și implementat în România de către Curba de Cultură.

Conscious cooking / Gătit conștient

/EN/ We all cause harm to the environment, just by being alive. Which is only more of a reason to try cutting down on it, for ourselves and the next generations. One area where that is very easy, but also necessary is our nourishment. The industrial agriculture is responsible for 18 % of all emissions and one of the biggest reasons for the deforestation of the Tropical Forests . Animal products are especially bad. In order to produce one kilo of meat, one must first invest 7-16 kilo of wheat or soy, soy that comes more often than not from fields that were previously the Brazilian rain forest. Another big cause of harm is the import of food products from other countries or sometimes even continents. They have to first cross the oceans and then be transported hundreds of kilometers in trucks to get to your local super market. Transports that cause tons of CO2 emissions to be pumped into the atmosphere.

I very much try to abide to these ideas while cooking. One of my favourite meals that does exactly that is Red Beet Soup. It’s a polish meal and I cook it after my mother’s recipe. While I never managed to make it quiet as good as she does, I still love cooking (and eating) it.

Ingredients:

- 1 red beet

- 3 big potatoes

- 1 carrot

- a cube of vegetable stock

- a bit of salt

You first peel the red beet, carrot and potatoes and cut them into small cubes.

Then cook the vegetables in water, till they are tender. While they are cooking add the cube of vegetable stock and a bit of salt.

Tipp: The soup tastes even better if you let it stand for a few hours and then rewarm it.

Another rather easy, but delicious recipe my mother thaught me, is her Southern German style potato salad. It is perfect as a side dish or appetizer.

- 1 big onion

- 1/2 big spoon sweet mustard

- 4 big potatoes

- 3 big spoons vinegar

- one cube of vegetable stock

- a bit of salt

Peel and cut the potatoes into big cubes. Cook them till they are tender. In the meanwhile cut the onions into pieces. Put half a glass of boiling water over the vegetable stock cube and mix it. Afterwards mix it with the vinegar, the mustard and the salt. Put the cooked potatoes, the mix and the onions into a big bowl and mix everything. Then put into the fridge for an hour.

/RO/ Cu toții cauzăm daune mediului înconjurător, pur și simplu prin a trăi. Ceea ce este doar un motiv în plus să încercăm să tăiem din asta, pentru noi și pentru generațiile viitoare. O zonă unde asta este foarte ușor, dar de asemenea necesar este hrănirea noastră. Agricultura industrială e responsabilă pentru 18 % din toate emisiile și unul dintre cele mai mari motive pentru deforestizarea Pădurilor Tropicale. Produsele animale sunt rele în mod special. Pentru a produce un kilogram de carne, trebuie investite 7-16 kilograme de grâu sau soia, soia care de cele mai multe ori vine din câmpuri care obișnuiau să fie Pădurea Tropicală Braziliană. O altă mare cauză de nocivitatea este importul de produse alimentare din alte țări sau uneori chiar alte continente. Trebuie întâi să treacă oceanele și apoi să fie transportate sute de kilometri în camioane pentru a ajunge la supermarket-ul vostru local. Transporturi care cauzează tone emisii de CO2 să fie pompate în atmosferă.

Încerc foarte mult să mă țin de aceste idei în timp ce gătesc. Una dintre mâncărurile mele favorite care face exact asta este Supa de Sfeclă Roșie. Este un preparat polonez și îl gătesc după rețetă mamei mele. Deși nu reușesc să o fac chiar așa de bună cum o face ea, tot iubesc să o gătesc (și să o mănânc).

Ingrediente:

- 1 sfeclă roșie

- 3 cartofi mari

- 1 morcov

- un cub de vegetable stock

- puțină sare

Pentru început curățați sfecla roșie, morcovii și cartofii și le tăiați în cuburi mici.

Apoi gătiți legumele în apă, până sunt fragede. În timp ce se gătesc adăugați cubul de stock de legume și puțină sare.

Pont: Supa are un gust chiar și mai bun dacă o lași să stea pentru câteva ore și apoi o reîncălzești.

O altă destul de ușoară, dar delicioasă rețetă pe care mama mea m-a învățat-o, este salata ei de cartofi în stil Sudic German. Este perfectă ca și garnitură sau aperitiv.

- 1 ceapă mare

- 1/2 lingură mare de muștar dulce

- 4 cartofi mari

- 3 linguri mari de oțet

- un cub de vegetable stock

- puțină sare

Curățați și tăiați cartofii în cuburi mari. Gătiții până sunt fragezi. Între timp tăiați ceapa în bucăți. Puneți jumătate de pahar de apă clocotită peste cubul de vegetable stock și amestecați. După aceea amestecați-l cu oțetul, muștarul și cu sarea. Puneți cartofii gătiți, mixul și ceapa într-un bol mare și amestecați totul. Apoi puneți în frigider pentru o oră.

A Day in Practica / O zi în practică

Once this August, there was “practica”, a two-week long joint project between six EVS volunteers engaged in environmental projects and four anthropology students from Bucureşti. Practica was a field research focussed on getting information about the waste management behaviour of the commune’s inhabitants. For that, we were listing and mapping trash bins and illegal trash dumps, interviewing people in the commune and observing the trash collection system.

So, on a certain Monday I was allocated to a group with Zenaida, Robert, Oana and Kristīne. The task for this day was to finish the mapping of bins and dumps that was started on the previous day, and my group was assigned to go around Schiuleşti in the morning.

We parked the car in front of the school and started to explore the lower part of the village. Soon, at the end of a small path, we found a hidden creek that was filled with all sorts of trash, ranging from plastics to textiles, together with some kilograms of rotten tomatoes.

Heading towards the bridge over Crasna river, we found a place above a steep slope with a very beautiful view over the valley, but leaning over to look down the abysm we encountered yet another place where the villagers secretly threw their garbage. Between plastic bottles, bags and rotting jeans, there were pumpkins blossoming as if somebody mistook trash for compost to grow their vegetables. In an attempt of admiring the view over the valley, on the other side of the river we could see a bright blue spot, whose rather unnatural colour suggested the presence of yet another trash hole.

On the return to the village a cute lonely black-and-beige-spotted puppy joined our group and made it a bit less sad to picture and map all the trashed places we encountered. After some time, we decided to head back to the village per se. Compared to the surroundings, the central streets of the village were rather clean when ignoring the desolate state of the pavement. We made our way up the dusty main road and headed to the park, where we left our new friend with a group of puppies that lives under the park’s recycling bins. A sudden rainstorm made us seek for shelter in Schiuleşti’s volunteers house, and as it continued raining for the rest of the morning we decided to return to the basecamp.

In the afternoon, the weather was good enough to continue the mapping, this time walking around Homorâciu. Again, a dog chose to accompany us along our way through the village. He looked battered, was limping and missing half of his tail. Probably he figured out that a group of friendly people would be the safest place to be.

At a crossing close to our house, we sensed a strong smell and found a place that looked like a deposit for trash that has been cleared shortly before. We chose to follow a road which was running parallel to a small creek. At some point, the asphalt ended and the road and the creek merged, leaving us all with wet feet. On the way down the creek/road we found two more places were trash was randomly dumped in the nature, but to our left we had a beautiful view over green and untrashed fields and hills, so that our martyrium was not in vain. The creek led us to Malu Vânăt, leaving us with a rather uneventful return up the main street and by the train station.

Arriving in Curba, a surprise was awaiting us: the screening of a documentary was planned as after dinner entertainment and to wrap up another eventful day.

Cândva în acest august, a fost ”practica”, un proiect cooperativ pe o durată de două săptămâni între șase voluntari SEV implicați în proiecte de mediu, și patru studenți la antropologie din București. Practica a fost o cercetare de teren axată pe obținerea de informații despre comportamentul de management al deșeurilor ai locuitorilor comunei. Pentru asta, listam și cartografiam coșuri de gunoi și locuri unde se depozitează gunoi în mod illegal, intervievam oameni din comună și observam sistemul de colectare al gunoiului.

Astfel, într-o anumită luni am fost alocat unui grup cu Zenaida, Robert, Oana și Kristīne. Sarcina pentru această zi a fost să terminăm cartografiatul coșurilor și spațiilor care a fost începută ziua trecută, și grupul meu a fost repartizat să se ducă prin Schiuleşti de dimineață.

Am parcat mașina în fața școlii și am început să explorăm părțile de jos ale satului. Curând, la sfârșitul unei mici cărări, am găsit o albie de râu ascunsă care era plină cu tot felul de gunoaie, variind de la plastic la textile, împreună cu niște kilograme de roșii putrezite.

Îndreptându-ne spre podul de deasuprea râului Crasna, am găsit un loc deasupra unei pante abrupte cu o vedere foarte frumoasă asupra văii, dar aplecându-ne să ne uităm în josul prăpastiei am dat de încă unul din locurile unde sătenii își aruncau gunoiul în secret. Printre sticle de plastic, pungi și blugi putreziți, erau dovleci înflorind de parcă cineva a confundat gunoiul cu compostul pentru a își crește legumele. Într-o încercare de a admira priveliștea de peste vale, pe cealaltă parte a râului am putut vedea un punct albastru și strălucitor, a cărui culoare nenaturală sugerează prezența încă unei gropi de gunoi.

La întoarcerea în sat, un cățeluș drăguț, singuratic, pestriț-cu-negru-și-bej, s-a alăturat grupului nostru și a facut să fie puțin mai puțin trist să facem poze și să cartografiem toate locurile pline de gunoi pe care le-am întâlnit. După un timp, am decis să ne întoarcem în sat în adevăratul sens al cuvântului. În comparație cu împrejurimile, străzile centrale ale satului erau destul de curate când ignorai starea neglijată a pavajului. Ne-am îndreptat către strada principală cea prăfuită și spre parc, unde l-am lăsat pe noul nostru prieten cu un grup de cățeluși care locuiesc sub coșurile de reciclare ale parcului. O ploaie bruscă ne-a făcut să căutăm adăpost în casa voluntarilor din Schiuleşti, și cum a continuat să plouă pentru restul dimineții am decis să ne întoarcem la tabăra de bază.

După-amiază, vremea a fost destul de bună încât să continuăm maparea, de data asta mergând prin Homorâciu. Din nou, un câine a ales să ne acompanieze de-a lungul drumului nostru prin sat. Arăta ponosit, schiopăta și îi lipsea jumate din coadă. Probabil s-a gândit că lângă un grup de oameni prietenoși ar fi cel mai în siguranță loc în care să fie.

La o intersecție aproape de casa noastră, am simțit un miros puternic și am găsit un loc care arăta ca un depozit pentru gunoi care a fost curățat de scurtă vreme. Am ales să urmărim un drum care mergea paralel cu un mic pârâu. La un moment dat, asfaltul s-a terminat, drumul și pârâul s-au unit, lăsându-ne pe toți cu picioarele ude. Pe drum în josul pârâului/drumului am mai găsit două locuri unde gunoiul a fost aruncat la întâmplare în natură, dar în stânga noastră aveam o frumoasă vedere asupra verzilor și nepangăritelor de gunoi câmpuri și dealuri, așa că martiriul nostru nu a fost în van. Pârâul ne-a condus la Malu Vânăt, lăsându-ne cu o întoarcere destul de monotonă pe strada principală și pe lângă gară.

Ajungând la Curbă, o surpriză ne aștepta: proiecția unui documentar plănuit ca divertisment de după cină și pentru a încheia încă o zi bogată în evenimente.

Tim este în România pentru o perioadă de șapte luni, din mai 2018 până în noiembrie 2018, în cadrul proiectului Building Youth supportive Communities – Environment [2017-2-RO01-KA105-037748] proiect co-finanțat de Uniunea Europeană prin Programul Erasmus+ și implementat în România de către Curba de Cultură.